State of the Matthew Address 2026

I am alive and well. As this is the baseline for me to give an address we will move swiftly on.

You can denounce Catholicism, but you can't get away from the fact that it's stories are some of the most moving shared narratives on the planet.

You can denounce Catholicism, but you can't get away from the fact that it's stories are some of the most moving shared narratives on the planet. And of those the Easter story represents one of the most significant narratives in all Christianity, chronicling Jesus Christ's final days, crucifixion, and resurrection. Throughout history, master artists have been inspired to capture these profound moments on canvas, creating works that have moved viewers for centuries. This visual journey through the Easter story allows us to experience its emotional depth and spiritual significance through the eyes of some of history's greatest painters.

Our journey begins with Palm Sunday, when Jesus entered Jerusalem to the acclaim of crowds who laid palm branches in his path. Giotto di Bondone's fresco from the Arena Chapel in Padua (c. 1305) depicts this moment with remarkable emotion. Unlike many formal Byzantine representations that preceded it, Giotto brings human feeling to the scene. Notice how the people in the trees cutting branches show excitement, while Jesus maintains a dignified calm, foreshadowing the more sombre events to come.

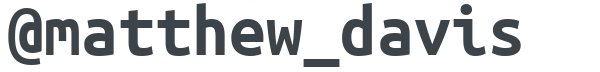

Perhaps the most famous depiction of Jesus sharing his final meal with his disciples comes from Leonardo da Vinci. Painted between 1495-1498 on the wall of the dining hall at the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, this masterpiece captures the dramatic moment when Jesus announces that one of his disciples will betray him.

Leonardo brilliantly organises the apostles in groups of three, each showing different reactions to the shocking news. The painting is renowned for its psychological insight and perfect one-point perspective. Notice how all lines in the composition lead to Christ at the centre, emphasising his central role in the unfolding drama.

After the Last Supper, Jesus retreated to the Garden of Gethsemane to pray, knowing what awaited him. El Greco's "Christ on the Mount of Olives" (1605) captures this moment of profound spiritual anguish with the artist's characteristic emotionally charged style.

The elongated figures, dramatic lighting, and swirling composition reflect Jesus's inner turmoil as he prays, "Father, if you are willing, take this cup from me; yet not my will, but yours be done." In the distance, we see Judas leading the soldiers who will arrest Jesus, adding to the painting's sense of impending tragedy.

Caravaggio's "The Taking of Christ" (1602) dramatises the moment of Jesus's arrest with the artist's revolutionary use of tenebrism, the dramatic contrast between light and dark. Judas's betrayal kiss happens in the centre of the composition, while chaotic movement swirls around this intimate moment.

The painting's dramatic lighting illuminates the expressions of the main figures while plunging others into shadow. Especially notable is the figure on the far right, believed to be a self-portrait of Caravaggio himself, who raises a lantern to witness the scene, perhaps involving the viewer in this moment of betrayal.

After his arrest, Jesus was brought before Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor. Antonio Ciseri's "Ecce Homo" (1871) depicts the moment when Pilate presents Jesus to the crowd, saying "Behold the man!" after Jesus had been scourged and crowned with thorns.

Ciseri uses a unique perspective in this painting. We view the scene from behind Pilate, looking out at the crowd demanding crucifixion. Jesus stands in quiet dignity despite his suffering, creating a powerful contrast with the angry mob. This perspective invites viewers to consider their own position in the narrative, are we with the crowd calling for crucifixion, or do we stand with the suffering Christ?

Among the countless depictions of the Crucifixion throughout art history, Paul Gauguin's "The Yellow Christ" (1889) offers a particularly thought-provoking interpretation. Based on a wooden crucifix in a chapel in Pont-Aven, Brittany, Gauguin places the crucifixion in the French countryside with Breton women praying nearby.

By removing the crucifixion from its historical setting, Gauguin suggests the timelessness and universality of Christ's sacrifice. The bright yellow used for Christ's body creates an otherworldly effect, suggesting divine light emanating from within, while the simplified forms and non-naturalistic colours demonstrate Gauguin's move toward Symbolism in art.

After Jesus died on the cross, his body was taken down and placed in the arms of his mother Mary. Michelangelo's "Pietà" (1498-1499), housed in St. Peter's Basilica, is perhaps the most moving artistic representation of this moment of profound grief.

Carved from a single block of marble when Michelangelo was just 24 years old, the sculpture achieves an impossible balance between naturalistic detail and idealised beauty. Mary appears younger than her years, symbolising her purity, while her expression conveys resigned acceptance rather than overwhelming grief. The smooth, polished surface of the marble gives the figures an ethereal quality, while the complex composition, with Mary's figure much larger than Jesus to accommodate his body across her lap, creates a sense of harmonious balance despite the tragic subject.

Following the Pietà, Jesus's body was prepared for burial and placed in a tomb. Raphael's "The Entombment" (1507) represents the young master's approach to this sombre moment with remarkable emotional and compositional sophistication.

Painted when Raphael was just 24 years old, this altarpiece demonstrates his ability to combine Renaissance principles of harmony and balance with profound emotional expression. The composition is divided into two integrated scenes: the carrying of Christ's body toward the tomb in the foreground, and the swooning of his mother Mary in the background, creating a powerful psychological connection between mother and son even in death.

Raphael arranges the bearers in a frieze-like procession that recalls classical reliefs, yet infuses the scene with a dynamic tension through the straining muscles of those carrying the weight of Christ's body. Unlike more static medieval representations, the figures here convey both physical exertion and emotional distress. Christ's body forms a diagonal across the composition, emphasising his lifelessness while also creating visual movement. The rich colours, particularly the reds and blues, add emotional intensity, while the beautiful landscape behind suggests nature's response to the divine tragedy.

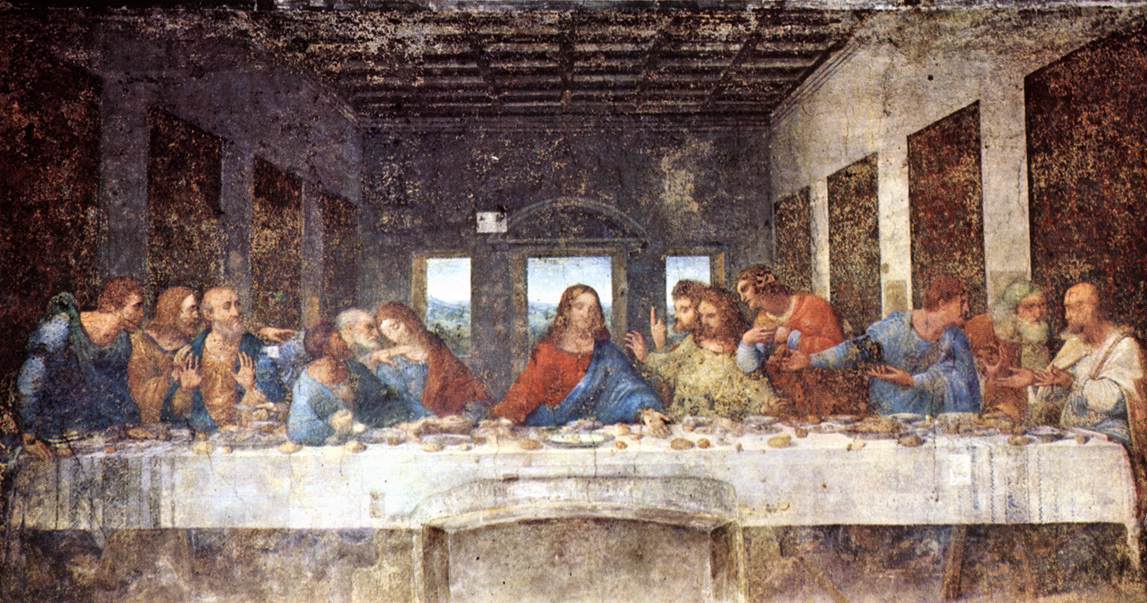

The culmination of the Easter story is, of course, the Resurrection. Piero della Francesca's fresco (c. 1463-1465) in the Civic Museum of Sansepolcro, Italy, presents one of the most powerful images of this transformative moment.

The painting is structured with mathematical precision, with Christ at the centre rising above four sleeping soldiers. His figure forms a perfect triangle, symbolising the Trinity, while his gaze is direct and powerful. The contrast between the dynamic, awakened Christ and the static, sleeping guards emphasises the supernatural nature of the event. The landscape behind them is divided between the barren winter trees on the left and the full, living trees on the right, symbolising the transition from death to life that the Resurrection represents.

The Easter story continues with Jesus appearing to his disciples after the Resurrection. Rembrandt's "The Supper at Emmaus" (1648) offers a contemplative and intimate portrayal of the moment when two disciples suddenly recognise that their mysterious dinner companion is the risen Christ.

Unlike more dramatic interpretations, Rembrandt uses his mastery of light and shadow to create a scene of quiet revelation. The soft, golden light emanating from Christ himself illuminates the humble interior, creating a sense of divine presence in an ordinary setting. One disciple reacts with subtle astonishment, while the other bows his head in reverence and realisation.

Rembrandt's Christ is not triumphant or idealised but deeply human and gentle. His face is partially shadowed, suggesting the mystery that still surrounds him even in this moment of revelation. The artist's characteristically rich impasto technique gives physical weight and presence to the scene, while the subdued colour palette creates an atmosphere of spiritual intimacy. A servant in the background remains oblivious to the miracle unfolding, a Rembrandt signature touch that reminds viewers that divine revelation comes to those prepared to receive it. The painting invites contemplation rather than dramatic reaction, encouraging viewers to participate in this moment of quiet epiphany.

Through these masterpieces spanning nearly seven centuries, we can trace the emotional and spiritual journey of the Easter story. Each artist brings their unique perspective, style, and cultural context to these pivotal moments, yet all illuminate aspects of this narrative that continues to resonate deeply across time and cultures.

What makes these works so powerful is not just their technical brilliance, but their ability to connect viewers directly to the human emotions within the divine story: grief, betrayal, sacrifice, wonder, and transcendent joy. In doing so, they fulfil one of the highest purposes of sacred art: to make the invisible visible, to give form to faith, and to help us contemplate mysteries that lie beyond words alone.

As we celebrate Easter, these masterpieces invite us to walk through this story once again, seeing it through fresh eyes and discovering new dimensions in its timeless message of suffering, sacrifice, and ultimately, the triumph of life over death.